DartUP 2021

Chris Gibb

Recovering Structural Typing EnthusiastNotes and Resources for the DartUP 2021 talk Fluttering Over the Air

It was a great privilege to be able to speak at DartUP 2021's English language track. Here you'll find the full slide deck used in the talk as well as the slide-by-slide speaker's notes I used. Once the video from the talk is published, It will be linked to here as well.

Good morning, good afternoon, good evening, good middle of the night. Good whatever time it is in whatever time zone you are in. My name is Chris Gibb. We're going to talk about codepush

Good morning, good afternoon, good evening, good middle of the night. Good whatever time it is in whatever time zone you are in. My name is Chris Gibb. We're going to talk about codepush

First of all, we’re going to describe what codepush means. What mobile distribution looks like today. We're going to try to frame the problem space with an example. We're going to describe some different technical approaches to codepush. Finally, we’re going to describe what I’m doing to innovate in this space.

First of all, we’re going to describe what codepush means. What mobile distribution looks like today. We're going to try to frame the problem space with an example. We're going to describe some different technical approaches to codepush. Finally, we’re going to describe what I’m doing to innovate in this space.

What is codepush? What does this term mean? I don’t believe there is any authoritative, industry standard definition of the term. To me, codepush means alternative distribution. Delivering an application update to users without using the app store on a given platform. I use the term app store broadly and interchangeably to refer either to the Google Play Store or Apple’s App Store here and in the rest of this talk. I would only consider a complete application update or significant changes to significant amounts of content (for some definition of significant) to count as codepush. Things like downloading new localizations or static images at runtime I would not consider to be codepush. There are quite a few different terms used to refer to codepush. Hot update, hot code, hot code push, codepush, out of band update. Over the air update. I believe OTA is a term us mobile application developers stole at some point from telephony firmware developers who in turn at some point co-opted it from embedded developers. I’m not sure of the precise etymology of the term but I know that we did not invent it.

What is codepush? What does this term mean? I don’t believe there is any authoritative, industry standard definition of the term. To me, codepush means alternative distribution. Delivering an application update to users without using the app store on a given platform. I use the term app store broadly and interchangeably to refer either to the Google Play Store or Apple’s App Store here and in the rest of this talk. I would only consider a complete application update or significant changes to significant amounts of content (for some definition of significant) to count as codepush. Things like downloading new localizations or static images at runtime I would not consider to be codepush. There are quite a few different terms used to refer to codepush. Hot update, hot code, hot code push, codepush, out of band update. Over the air update. I believe OTA is a term us mobile application developers stole at some point from telephony firmware developers who in turn at some point co-opted it from embedded developers. I’m not sure of the precise etymology of the term but I know that we did not invent it.

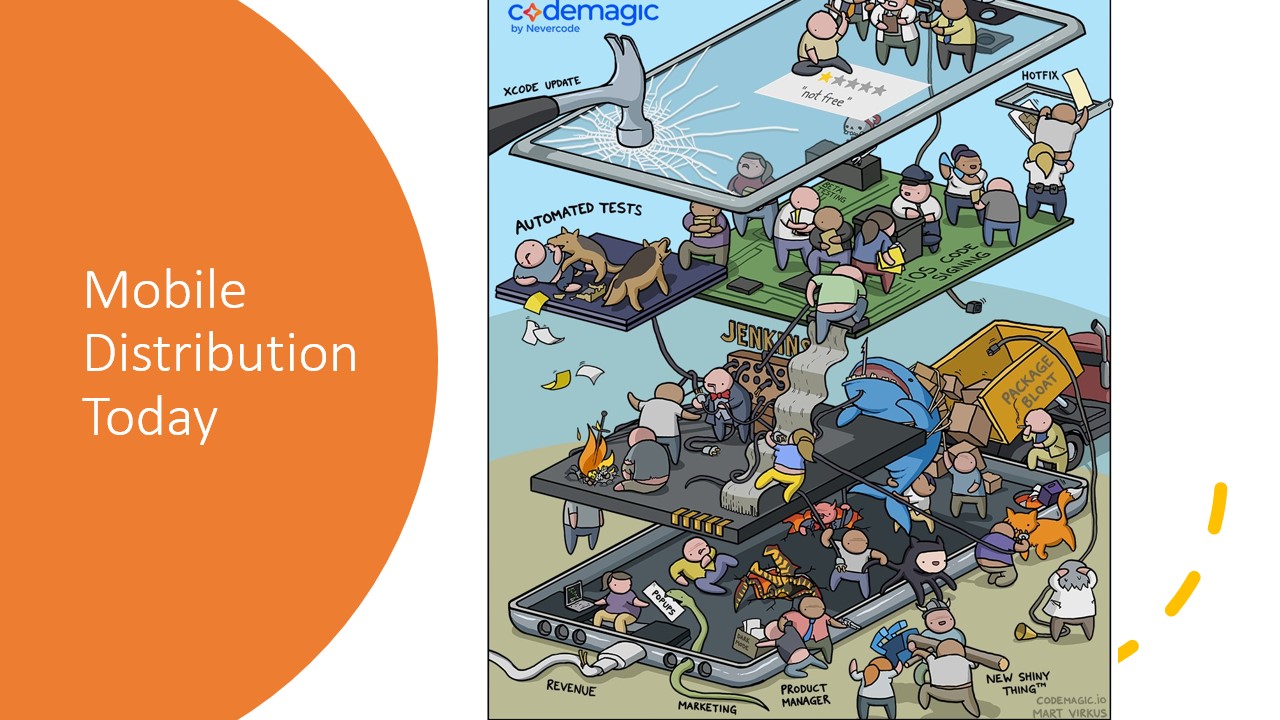

With that all out of the way. What does mobile distribution look like today? Well, it looks a little something like this. I’m not affiliated in any way with CodeMagic but I believe that this image perfectly captures what it feels like to build and ship a mobile application. Build some globs of machine code (and or Dalvik bytecode, and or LLVM bitcode as the case may be), archive it together with some static images and other assets and sign it all. Submit it to the app store. Wait for review and approval. Wait for rollout. This model is painful. We end up with a long tail of releases. Just because our shiny new release is available in a given users market does not mean they will uptake it. There is very little we can do to incentivize or force users to uptake new versions. This in turn makes deprecating backend APIs that support our apps very tricky. You need solid data on active users and their app versions to make those decisions safely. Strict upgrade ordering can’t be enforced for those users that do uptake new versions. A user on version 1 may upgrade straight to version 100. If client side data is involved, version 100 will need to maintain migrations for the previous 99 app versions lest a user find themselves with a bricked install.

With that all out of the way. What does mobile distribution look like today? Well, it looks a little something like this. I’m not affiliated in any way with CodeMagic but I believe that this image perfectly captures what it feels like to build and ship a mobile application. Build some globs of machine code (and or Dalvik bytecode, and or LLVM bitcode as the case may be), archive it together with some static images and other assets and sign it all. Submit it to the app store. Wait for review and approval. Wait for rollout. This model is painful. We end up with a long tail of releases. Just because our shiny new release is available in a given users market does not mean they will uptake it. There is very little we can do to incentivize or force users to uptake new versions. This in turn makes deprecating backend APIs that support our apps very tricky. You need solid data on active users and their app versions to make those decisions safely. Strict upgrade ordering can’t be enforced for those users that do uptake new versions. A user on version 1 may upgrade straight to version 100. If client side data is involved, version 100 will need to maintain migrations for the previous 99 app versions lest a user find themselves with a bricked install.

Consider our brand-new counting app startup, “Prestige Counting”. We’re moving fast, we’re listening to users. We’re trying desperately to find product-market fit in the US market. No matter how fast our development team is iterating on feedback and releasing updates, our iteration time is only as fast as app store review and rollout will allow. Before I get a triumphant twitter message from someone mentioning any of the below services, they don’t apply to the scenario I’ve outlined. Things like MDM/or enterprise distribution options only apply to enterprise users. Play Store tracks, testflight, firebase, testfairy and the like apply only to those users who are already enthusiastic about your app and are willing to live on the edge of your offering.

Consider our brand-new counting app startup, “Prestige Counting”. We’re moving fast, we’re listening to users. We’re trying desperately to find product-market fit in the US market. No matter how fast our development team is iterating on feedback and releasing updates, our iteration time is only as fast as app store review and rollout will allow. Before I get a triumphant twitter message from someone mentioning any of the below services, they don’t apply to the scenario I’ve outlined. Things like MDM/or enterprise distribution options only apply to enterprise users. Play Store tracks, testflight, firebase, testfairy and the like apply only to those users who are already enthusiastic about your app and are willing to live on the edge of your offering.

Let’s jump forward a bit. Let’s imagine our hot new counting app startup has made it. We’ve got millions of daily active users. We’ve captured the US market with our core offering. As a Canadian myself, our far lower temperatures and far higher maple syrup consumption tend to make us on average fickler than our southern counterparts. Prestige counting is trialing a new “multiply” feature for the Canadian market. As well, a small trial with an international airport. Looking to break into the B2B and enterprise space. All of the wonderful reliability and governance challenges that come along with it.

Let’s jump forward a bit. Let’s imagine our hot new counting app startup has made it. We’ve got millions of daily active users. We’ve captured the US market with our core offering. As a Canadian myself, our far lower temperatures and far higher maple syrup consumption tend to make us on average fickler than our southern counterparts. Prestige counting is trialing a new “multiply” feature for the Canadian market. As well, a small trial with an international airport. Looking to break into the B2B and enterprise space. All of the wonderful reliability and governance challenges that come along with it.

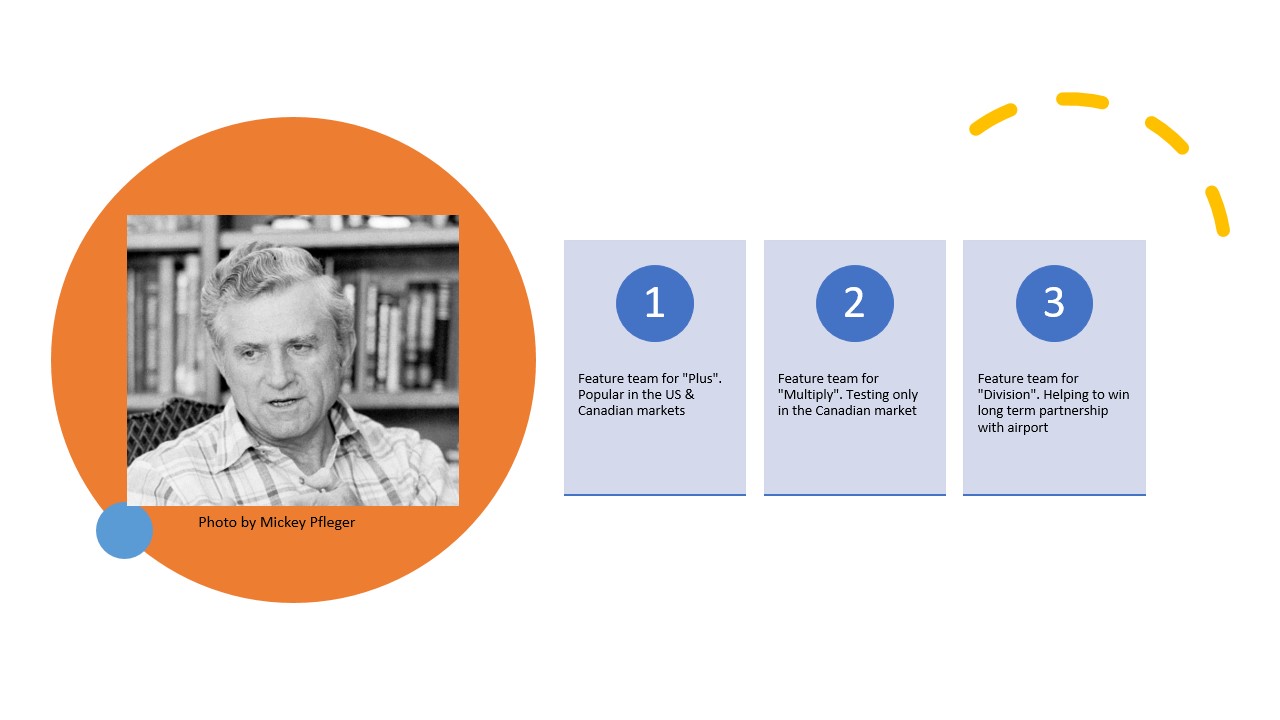

If we examine the feature teams trying to execute along all these priorities now, we’ll see 3 distinct teams. Team number one is focused on maintaining and expanding on our core offering which is our “plus” feature. Team number two is focused exclusively on testing the Canadian market with the “multiply” feature. Team number three is focused on the “division” feature as well as other tasks like hardening the security of the app, expanding handset support to include the core OEMs and device models that our airport deploys internally. I will admit, the work of team number one does impact team number two and team number three. Team number two’s work is independent of team number 1 and 3, and likewise, team number three’s work is independent of team number 1 and 2. In spite of this independence, the path to production for every single team is still the app store. What does this situation remind you of? Amdahl’s law! This appears to be an application of Amdahl’s law. Full points if you had guessed Gustafon’s law or the law of diminishing returns or related. This is an image of Dr. Amdahl at his home taken in 1967 making a rather confused face. This is exactly the face I made when I was first confronted with this problem. Each team can move as fast as they want, as independently as they want. Ultimately, they can only ship as fast as app store review and rollout will allow for, through the single distribution channel the app store allows for.

If we examine the feature teams trying to execute along all these priorities now, we’ll see 3 distinct teams. Team number one is focused on maintaining and expanding on our core offering which is our “plus” feature. Team number two is focused exclusively on testing the Canadian market with the “multiply” feature. Team number three is focused on the “division” feature as well as other tasks like hardening the security of the app, expanding handset support to include the core OEMs and device models that our airport deploys internally. I will admit, the work of team number one does impact team number two and team number three. Team number two’s work is independent of team number 1 and 3, and likewise, team number three’s work is independent of team number 1 and 2. In spite of this independence, the path to production for every single team is still the app store. What does this situation remind you of? Amdahl’s law! This appears to be an application of Amdahl’s law. Full points if you had guessed Gustafon’s law or the law of diminishing returns or related. This is an image of Dr. Amdahl at his home taken in 1967 making a rather confused face. This is exactly the face I made when I was first confronted with this problem. Each team can move as fast as they want, as independently as they want. Ultimately, they can only ship as fast as app store review and rollout will allow for, through the single distribution channel the app store allows for.

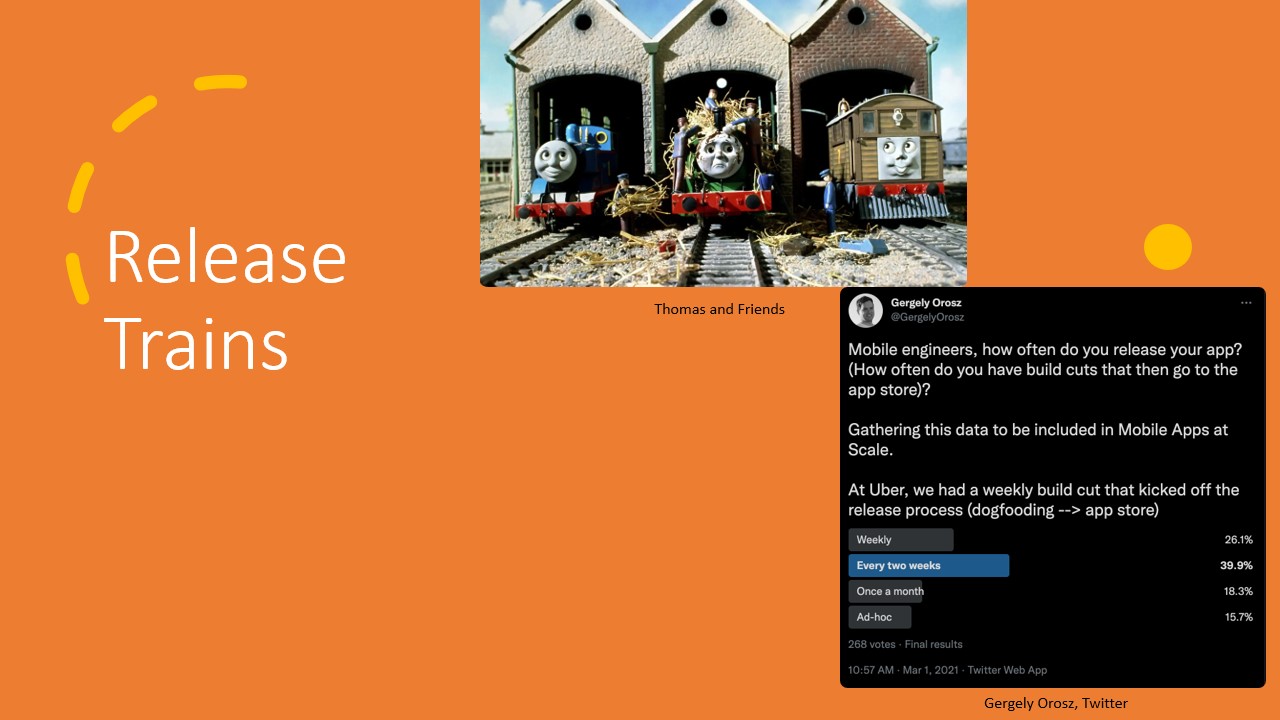

How do we solve this? One approach is release trains. Gergely Orosz, aka “The Pragmatic Engineer”. The author of “Building Mobile Apps at Scale” (among other great books), conducted a Twitter poll in Q1 of this year. He asked the Twitter mob how often they release their apps with the most popular response being every two weeks. Every two weeks, whatever work is ready, is built and included in a process leading up to being released on the app store. This process, broadly is referred to as a release train. Release trains tend to look different at every organization. At Uber for instance, Gergely alludes to the two-week process including internal dogfooding of the Uber apps wherein every employee is always using the most recent release train build of the app. At organizations whose apps are not primarily B2C, long-running (think tens of hours or days) worth of automated UI integration tests and/or exhaustive manual tests are performed. The point being: quality. Once that release is live, it will live forever. It is imperative that it is high quality. This in turn, can lead to a new pain point. “Release fever”. Member of the C++ ISO committee Corentin Jabot, talking about the release cycle of new editions of the C++ language standard coined the term “release fever” to describe the phenomenon of changes having their quality reduced in order to make it on time in order to be included in a release. This is absolutely something that a release train model can cause. As we can see in this graphic, our left most train leaves the station on time and happy. Middle train has just missed the cutoff and is covered in hay and very sad. Right most train wasn’t going to be ready anyway and is pleased to continue working.

How do we solve this? One approach is release trains. Gergely Orosz, aka “The Pragmatic Engineer”. The author of “Building Mobile Apps at Scale” (among other great books), conducted a Twitter poll in Q1 of this year. He asked the Twitter mob how often they release their apps with the most popular response being every two weeks. Every two weeks, whatever work is ready, is built and included in a process leading up to being released on the app store. This process, broadly is referred to as a release train. Release trains tend to look different at every organization. At Uber for instance, Gergely alludes to the two-week process including internal dogfooding of the Uber apps wherein every employee is always using the most recent release train build of the app. At organizations whose apps are not primarily B2C, long-running (think tens of hours or days) worth of automated UI integration tests and/or exhaustive manual tests are performed. The point being: quality. Once that release is live, it will live forever. It is imperative that it is high quality. This in turn, can lead to a new pain point. “Release fever”. Member of the C++ ISO committee Corentin Jabot, talking about the release cycle of new editions of the C++ language standard coined the term “release fever” to describe the phenomenon of changes having their quality reduced in order to make it on time in order to be included in a release. This is absolutely something that a release train model can cause. As we can see in this graphic, our left most train leaves the station on time and happy. Middle train has just missed the cutoff and is covered in hay and very sad. Right most train wasn’t going to be ready anyway and is pleased to continue working.

To briefly recap everything we’ve just talked about. Distribution takes a long time. Review and rollout time is measured in days to weeks. Releases live forever. The quality of each release is absolutely critical. This leads to lengthy CI and QA processes. Further adding to the time it takes to distribute a given change. What we need as mobile developers therefore is some form of alternative distribution.

To briefly recap everything we’ve just talked about. Distribution takes a long time. Review and rollout time is measured in days to weeks. Releases live forever. The quality of each release is absolutely critical. This leads to lengthy CI and QA processes. Further adding to the time it takes to distribute a given change. What we need as mobile developers therefore is some form of alternative distribution.

Flutter by its nature makes this hard. Dart AOT is optimized to produce small executables that exhibit fast startup. It favors low latency over aggregate throughput. These are all qualities we expect from our apps and a big part of what makes Flutter so great. Flutter makes JIT release builds hard to do out of the box. JITing is banned on iOS anyway, so this is not a viable option. Flutter interpreter only builds are not possible. Even if they were, they would perform poorly. Deferred components don’t count as an alternative distribution method. Code that was not present during the initial build cannot be introduced using a deferred component.

Flutter by its nature makes this hard. Dart AOT is optimized to produce small executables that exhibit fast startup. It favors low latency over aggregate throughput. These are all qualities we expect from our apps and a big part of what makes Flutter so great. Flutter makes JIT release builds hard to do out of the box. JITing is banned on iOS anyway, so this is not a viable option. Flutter interpreter only builds are not possible. Even if they were, they would perform poorly. Deferred components don’t count as an alternative distribution method. Code that was not present during the initial build cannot be introduced using a deferred component.

If Flutter makes Dart AOT the only viable option for release builds, let's explore some methods to work with Dart AOT instead of fighting it. There are a few broad approaches I’ve seen in the community at large. UI as configuration, embedded web content, native VM written in C, C++ or some other language, communicating with Dart AOT code through FFI or some other method like Platform Channels. VM written in Dart.

If Flutter makes Dart AOT the only viable option for release builds, let's explore some methods to work with Dart AOT instead of fighting it. There are a few broad approaches I’ve seen in the community at large. UI as configuration, embedded web content, native VM written in C, C++ or some other language, communicating with Dart AOT code through FFI or some other method like Platform Channels. VM written in Dart.

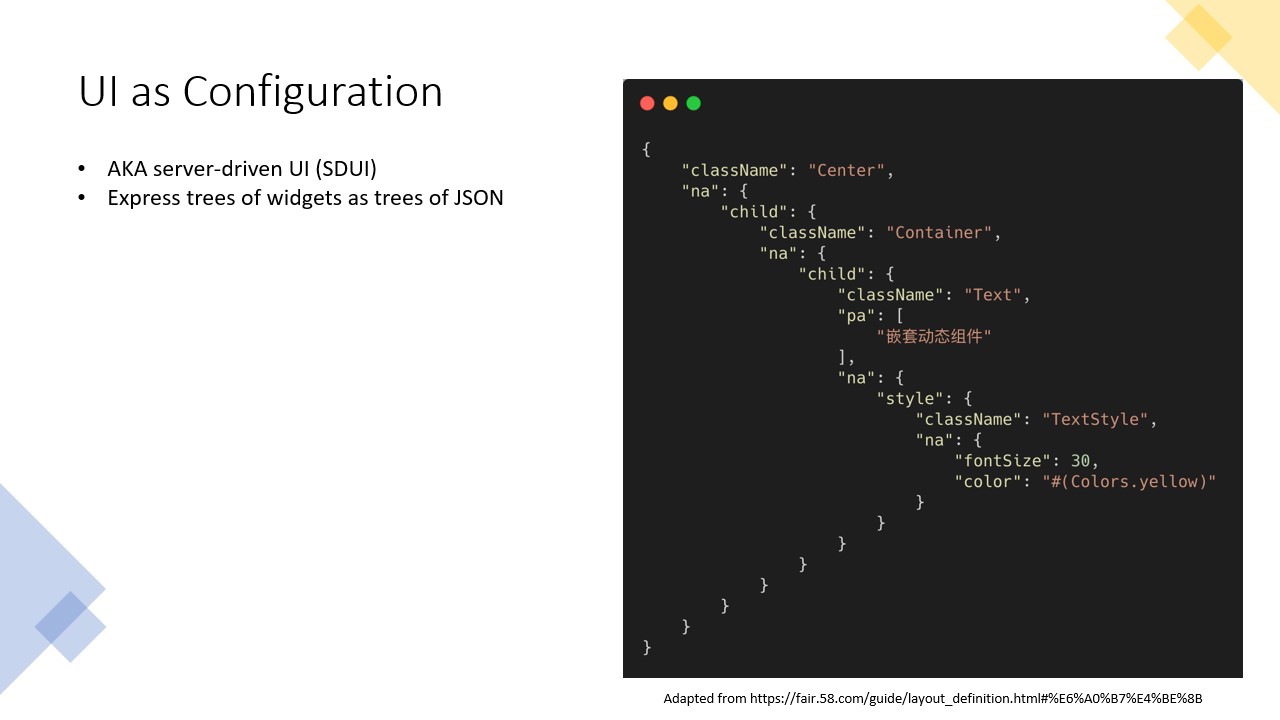

Also referred to as SDUI (server-driven UI). Instead of expressing UI as trees of widgets, UI is expressed as trees of configuration. You could imagine this configuration could be provided to an app at runtime over the network, allowing the UI to change without a new app version being released. On the right of this slide is an example adapted from the documentation of a project called Fair which aims to enable exactly this. This snippet describes a Center widget, with a Container and a Text widget with yellow text which reads something to the effect of “nested dynamic components”. Fair is an open-source project maintained by Chinese life service platform 58.com. It works by resolving trees of JSON into concrete objects at runtime. Resolvers are created by a compiler that integrates with Dart’s build_runner. This compiler is in turn driven by annotations. Users annotate both first-party and third-party widgets they would like to be able to resolve at runtime and the compiler does the rest. Fair however does not handle logic very well. There is a small class-based DSL that allows for expressing some small operations like boolean conditions and mapping iterables. In general, Fair is mostly concerned about UI. Another strong example in this category (though not open-source as far as I can tell) is the efforts that Chinese voucher and O2O life service platform Meituan has made. Meituan has blogged at length about the extent of their solution. Along the same lines as Fair though with what appears to be some incredibly rich static analysis that allows Meituans compiler to produce resolvers that include AST interpreters for a large subset of Dart and IDE hints when developers produce annotated code that will be rejected by the compiler. Meituan also appears to have built a very strong observability and operations platform to monitor the performance and behaviour of their deployed configurations in production. I gave only a brief overview of two organizations working on SDUI in Flutter. There a lot of people working in this space both for Flutter and other ecosystems and both open and closed source.

Also referred to as SDUI (server-driven UI). Instead of expressing UI as trees of widgets, UI is expressed as trees of configuration. You could imagine this configuration could be provided to an app at runtime over the network, allowing the UI to change without a new app version being released. On the right of this slide is an example adapted from the documentation of a project called Fair which aims to enable exactly this. This snippet describes a Center widget, with a Container and a Text widget with yellow text which reads something to the effect of “nested dynamic components”. Fair is an open-source project maintained by Chinese life service platform 58.com. It works by resolving trees of JSON into concrete objects at runtime. Resolvers are created by a compiler that integrates with Dart’s build_runner. This compiler is in turn driven by annotations. Users annotate both first-party and third-party widgets they would like to be able to resolve at runtime and the compiler does the rest. Fair however does not handle logic very well. There is a small class-based DSL that allows for expressing some small operations like boolean conditions and mapping iterables. In general, Fair is mostly concerned about UI. Another strong example in this category (though not open-source as far as I can tell) is the efforts that Chinese voucher and O2O life service platform Meituan has made. Meituan has blogged at length about the extent of their solution. Along the same lines as Fair though with what appears to be some incredibly rich static analysis that allows Meituans compiler to produce resolvers that include AST interpreters for a large subset of Dart and IDE hints when developers produce annotated code that will be rejected by the compiler. Meituan also appears to have built a very strong observability and operations platform to monitor the performance and behaviour of their deployed configurations in production. I gave only a brief overview of two organizations working on SDUI in Flutter. There a lot of people working in this space both for Flutter and other ecosystems and both open and closed source.

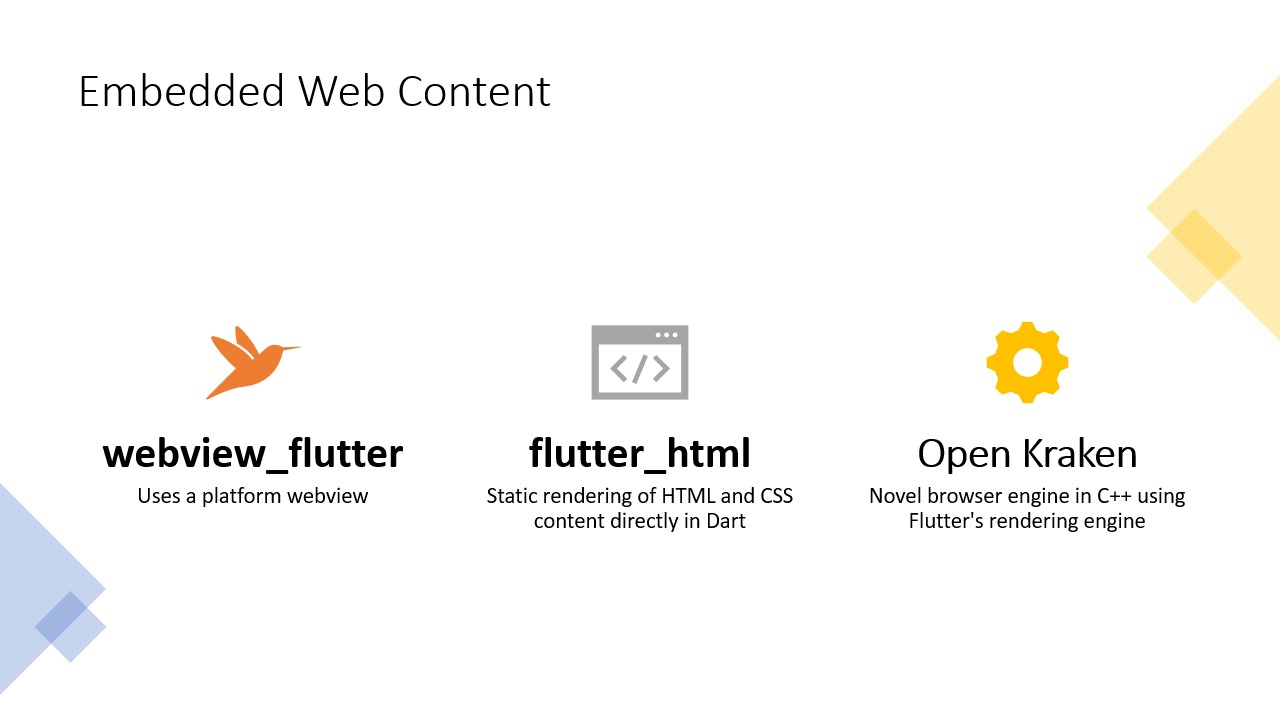

As SDUI tends to greatly constrain expressiveness, a natural next option is embedded web content. As an attempt to bring all the familiar ideas and patterns of the web (as well as, ideally, turing completeness) into something that can enable a codepush like experience. Something like the webview_flutter package could be used for this purpose. Take a platform webview, and integrate it into the widget tree. You could even host flutter web content. The Flutter_html package is a different approach. Instead of using platform webviews, provide an HTML/CSS rendering environment directly in Flutter. It also allows for adding extra tags. Though, does not provide for any kind of Javascript execution. Open Kraken is an ambitious open-source project backed by Alibaba and apparently already being used in production by subsidiaries like Taobao, Youku and TMall. Open Kraken builds a novel browser engine ontop of Flutter’s Skia graphics library. All implemented in C++. Open Kraken supports custom HTML tags implemented in Flutter as well Javascript execution backed by QuickJS with support for direct bytecode execution, and rich Javascript method channels. I couldn’t find icons for these projects, so this is indeed clip art.

As SDUI tends to greatly constrain expressiveness, a natural next option is embedded web content. As an attempt to bring all the familiar ideas and patterns of the web (as well as, ideally, turing completeness) into something that can enable a codepush like experience. Something like the webview_flutter package could be used for this purpose. Take a platform webview, and integrate it into the widget tree. You could even host flutter web content. The Flutter_html package is a different approach. Instead of using platform webviews, provide an HTML/CSS rendering environment directly in Flutter. It also allows for adding extra tags. Though, does not provide for any kind of Javascript execution. Open Kraken is an ambitious open-source project backed by Alibaba and apparently already being used in production by subsidiaries like Taobao, Youku and TMall. Open Kraken builds a novel browser engine ontop of Flutter’s Skia graphics library. All implemented in C++. Open Kraken supports custom HTML tags implemented in Flutter as well Javascript execution backed by QuickJS with support for direct bytecode execution, and rich Javascript method channels. I couldn’t find icons for these projects, so this is indeed clip art.

This provides a good segue into the next category which is JS VMs. It could be argued that Open Kraken would fall into this category as well given its integration of QuickJS. The only other project taking this approach I’ve encountered is MxFlutter, backed by Tencent. MxFlutter uses either Javascript Core on iOS or V8 on Android and provides bindings for a large number of Flutter classes and functions. Enabling developers to write Flutter content in Javascript and integrate it into the widget tree.

This provides a good segue into the next category which is JS VMs. It could be argued that Open Kraken would fall into this category as well given its integration of QuickJS. The only other project taking this approach I’ve encountered is MxFlutter, backed by Tencent. MxFlutter uses either Javascript Core on iOS or V8 on Android and provides bindings for a large number of Flutter classes and functions. Enabling developers to write Flutter content in Javascript and integrate it into the widget tree.

My last category is VMs written in Dart. With VMs written in C++ or some other language, the only way to communicate with Dart code is either through FFI or Platform channels. This tends to greatly limit both the richness and performance of interop. Having the VM be written in Dart makes interop a far easier problem to solve. Though sound, reified types tend to still complicate things somewhat. The dart_eval package aims to provide an AST interpreter for Dart. The apollovm package similarly aims to provide an AST interpreter for Dart but also for Java11. Hetu is a novel scripting language designed and built to allow for writing and distributing dynamic content in Flutter. It provides a bytecode VM, compiler, binding generator and IDE plugins. These projects all appear to be relatively early in their development but have tremendous promise.

My last category is VMs written in Dart. With VMs written in C++ or some other language, the only way to communicate with Dart code is either through FFI or Platform channels. This tends to greatly limit both the richness and performance of interop. Having the VM be written in Dart makes interop a far easier problem to solve. Though sound, reified types tend to still complicate things somewhat. The dart_eval package aims to provide an AST interpreter for Dart. The apollovm package similarly aims to provide an AST interpreter for Dart but also for Java11. Hetu is a novel scripting language designed and built to allow for writing and distributing dynamic content in Flutter. It provides a bytecode VM, compiler, binding generator and IDE plugins. These projects all appear to be relatively early in their development but have tremendous promise.

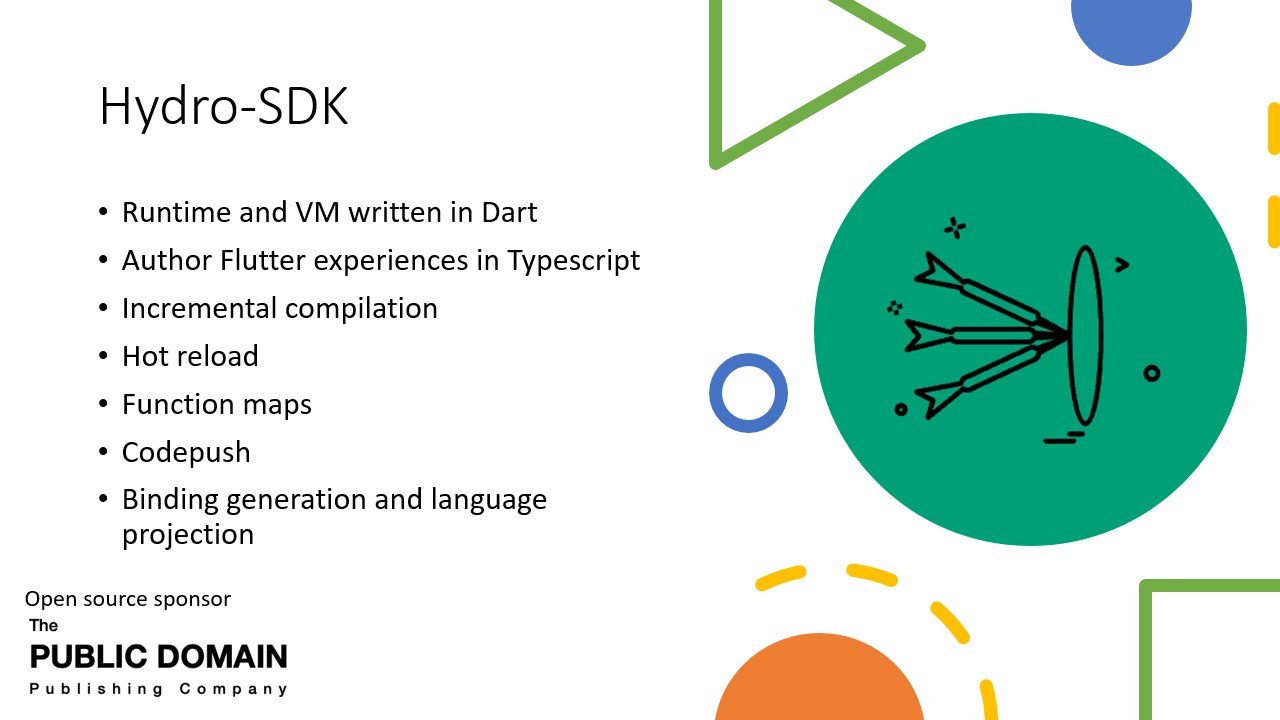

Why do I spend so much time in this space, why do I know these things? What am I doing to innovate in this space? My passion project of the last just about 2 years has been Hydro-SDK. Hydro-SDK is a toolchain, virtual machine and runtime system all written in Dart. It allows developers to author Flutter experiences in TypeScript in much the same way as we’re used to in Dart. It provides things like incrementally compiling TypeScript, hot reloading of TypeScript in a running Flutter app, function maps (not quite source maps) and an integrated, hosted codepush service (though this service is still an early MVP). In talking about approaches to alternative distribution to enable codepush, what we’re really talking about is building up a foreign execution environment and ultimately a foreign development environment. These foreign environments need to be cleanly and deeply integrated into the environments that developers are already familiar with. For us Flutter developers, that is Dart and Dart AOT. The last point here, about binding generation and language projection, is about building tools to produce these environments automatically given a Dart package. I don’t have time in this talk to also dive into this topic. I’ve spent the last 15 months on this alone and it probably deserves a dedicated talk. The PUBLIC DOMAIN Publishing Company has been a generous sponsor for the last year via Github sponsors

Why do I spend so much time in this space, why do I know these things? What am I doing to innovate in this space? My passion project of the last just about 2 years has been Hydro-SDK. Hydro-SDK is a toolchain, virtual machine and runtime system all written in Dart. It allows developers to author Flutter experiences in TypeScript in much the same way as we’re used to in Dart. It provides things like incrementally compiling TypeScript, hot reloading of TypeScript in a running Flutter app, function maps (not quite source maps) and an integrated, hosted codepush service (though this service is still an early MVP). In talking about approaches to alternative distribution to enable codepush, what we’re really talking about is building up a foreign execution environment and ultimately a foreign development environment. These foreign environments need to be cleanly and deeply integrated into the environments that developers are already familiar with. For us Flutter developers, that is Dart and Dart AOT. The last point here, about binding generation and language projection, is about building tools to produce these environments automatically given a Dart package. I don’t have time in this talk to also dive into this topic. I’ve spent the last 15 months on this alone and it probably deserves a dedicated talk. The PUBLIC DOMAIN Publishing Company has been a generous sponsor for the last year via Github sponsors

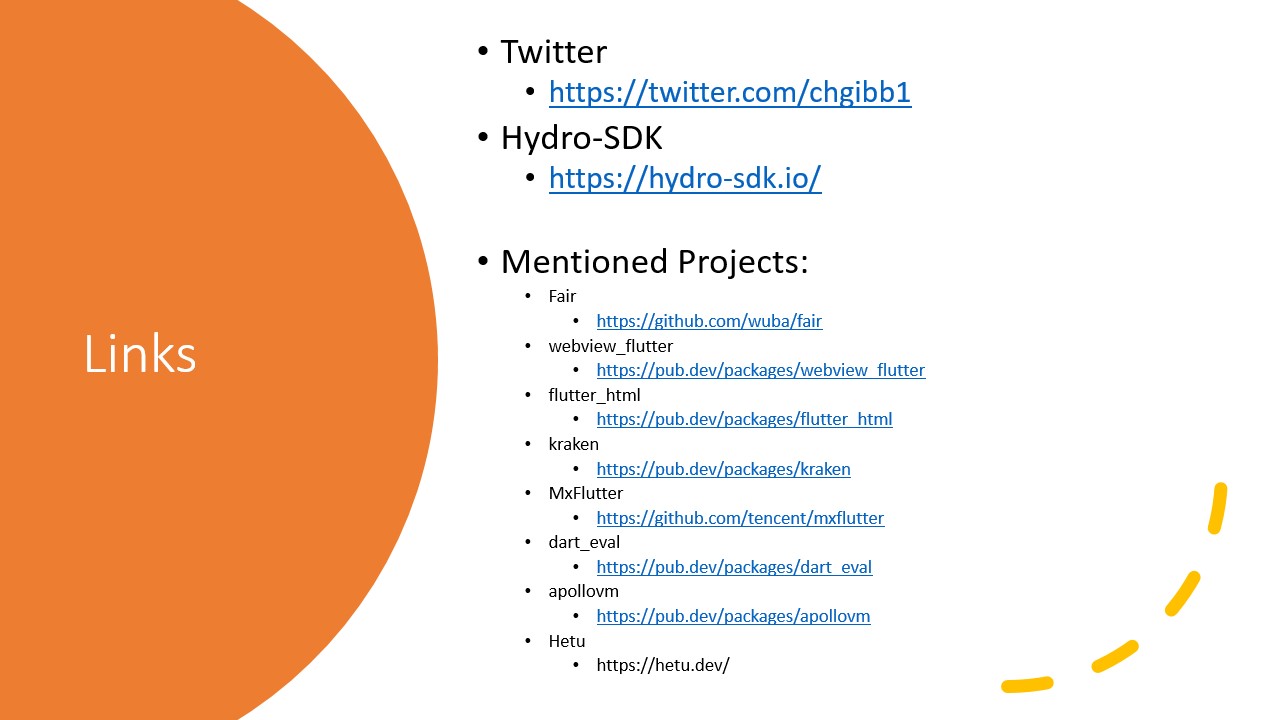

Twitter

Hydro-SDK

Mentioned Projects:

Fair

webview_flutter

flutter_html

kraken

MxFlutter

dart_eval

apollovm

Hetu